How I could've taken over the production server of a Yahoo acquisition through command injection

On the night of May 20th I had begun to develop a small headache and neck pains after spending days looking at Yahoo's messenger application. I couldn't get a grasp of how it operated, so I stepped outside and made the decision to find a new target. Something that interested me was the fact that a user named meals was banned after 'overstepping his boundaries' while participating in Yahoo's bug bounty program.

After walking back inside and speaking to my friend Thomas (dawgyg) we decided that it'd be a good idea to look at the program Sean was looking at right before he got banned.

Step 1: Reconnaissance

The scope of the acquisition detailed in Sean's whitepaper was very simple:

*.mediagroupone.de

*.snacktv.de

*.vertical-network.de

*.vertical-n.de

*.fabalista.com

Although many domains were listed, it appeared that Sean had primarily targeted the content management system of SnackTV for the majority of his report. Me and Thomas decided to restructure the approach and target the www portion of SnackTV because Thomas had previously spent time on the platform and found a few blind XSS vulnerabilities. The platform seemed different than most because of the fact that it was (1) a German company and (2) a developer network for video producers -- not standard Yahoo users.

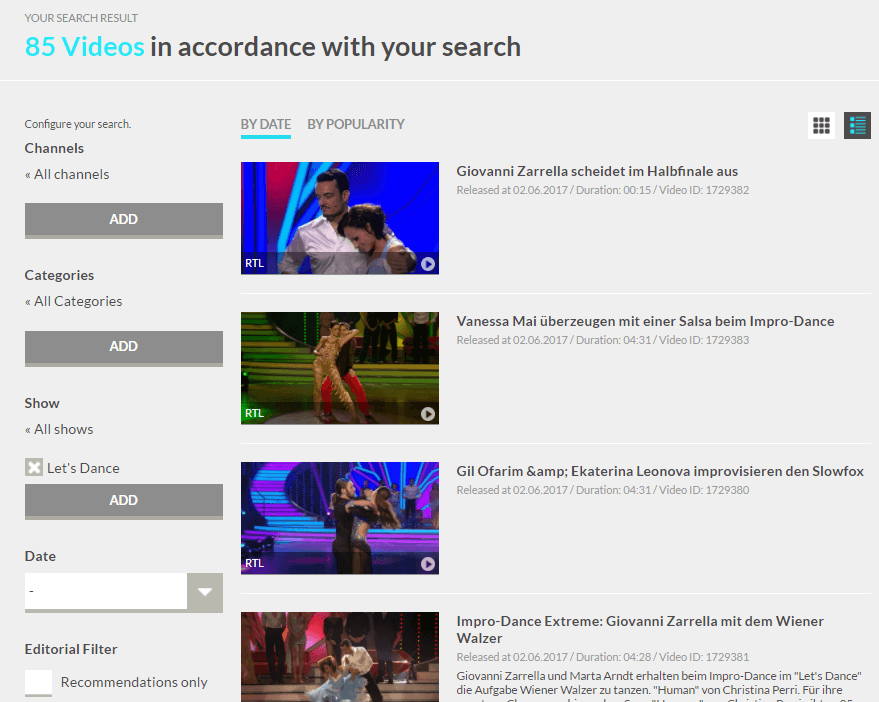

The search page of SnackTV. It's apparent that this is a video network, but the registration had to be manually reviewed and therefore we had no direct access to the upload panel on the site.

While Thomas was busy automating the scanning portion of our project, I spent some time getting a feel for the application (understanding how something i_s supposed to operate_ is usually a prerequisite to understanding how it isn't supposed to operate).

Step 2: Scanning

Something that both me and Thomas do when looking at new scope is run background tasks specific to the application. The tools "subbrute" and "dirsearch" are my go-to scripts for passive identification of both (1) direct vulnerabilities and (2) potentially vulnerable content. Understanding how to use tools like this will aid any pentester while they're on the hunt for vulnerabilities.

After running these tools for a long while we received a lot of output that didn't help much. Most of the information was very standard like ".htpasswd" being blocked behind a standard HTTP 403 error, "admin" being blocked behind a redirect to a login panel, etc. Eventually, however, we did get a hit using a ridiculously large word-list paired with the "dirsearch" script.

The file name in question was "getImg.php" hiding behind the "imged" directory (http://snacktv.de/imged/getImg.php). After some looking around we realized that this file was publicly accessible through the Google dork "site:snacktv.de filetype:php". This step was very important because the vulnerable file required GET parameters in order to return content. The discovered GET parameters would've taken weeks to brute force or guess, and no-one wants to do that because they're often paired with additional secondary parameters that must be present for the query to execute.

Example logic regarding required GET parameters

http://example.com/supersecretdevblog.php - 500 Internal Server error... you must have parameters to see this content! http://example.com/supersecretdevblog.php?page=index&post=1 - 200 OK... <p>how I hax0r'd the president and stole his DOB - <b>CONFIDENTIAL</b></p>

What we knew up to this point:

- The file "getImg.php" took multiple HTTP GET parameters that would auto-download a modified image file if supplied with a link to an image through the "imgurl" parameter.

- The parameters present on the Google search reeked of ImageMagick's cropping function.

Step 3: Access and escalation

The first thing we thought of when we saw this was "ImageTragick" (CVE-2016-3714) and decided to send it a few test payloads.

Thomas and I spent hours crafting image files that contained payloads specific to the vulnerability. The way it worked was that a hot image file (an image file that contained a payload) would be processed by the command line tool "ImageMagick" then accidentally execute arbitrary commands because it lacked sanitation. None of our payloads worked and eventually we both got kind of tired of looking at it. Is it possible that they could be running the post-fix version on such a strange file?

<?xml version="1.0" standalone="no"?>

<!DOCTYPE svg PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD SVG 1.1//EN" "http://www.w3.org/Graphics/SVG/1.1/DTD/svg11.dtd";>

<svg width="640px" height="480px" version="1.1" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg"; xmlns:xlink= "http://www.w3.org/1999/xlink";>

<image xlink:href="**https://example.com/image.jpg**"|ls "-la" x="0" y="0" height="640px" width="480px"/> </svg>

An example payload that we sent to the server. This would be sent to the server via one of our personal domains after uploading it and fetching it with the "imageurl" parameter. The goal was to make it execute an arbitrary command. Take note of the image xlink:href URL in bold.

There was nothing unusual except the way the server processed the file destination URL. We'd send it random text files and it'd still return the same data from the last call. Based on the vulnerability disclosure details and all the content we read about "ImageMagick" it seemed this was either not vulnerable or not ImageMagick. We took a break from attacking the specific file and decided to look elsewhere.

It was maybe 3:30 AM and we'd found a few stored cross site scripting vulnerabilities, HTTP 401 response injection flaws, and general mismanagement issues but nothing critical. When you're doing bug bounty and eyeing an acquisition it kind of sucks because most bounties are going to be significantly scaled down due to the fact the impact is so low. In some peoples eyes it's still fruitful to receive the reduced bounties but in others it may be just a waste of time compared to the delving list of privates programs they have access to. The single benefit to targeting acquisitions is the fact that many people completely leave them out of scope.

After going back to the URL I got kind of bored and questioned the implementation. What if Yahoo, instead of processing the image as a whole, was somehow injecting the URL into a XML "image xlink:href" like the proof of concept content? What payloads should I try to validate this?

In my browser I appended a single double quote character and saw some interesting output...

REQUEST

GET /imged/getImg.php?imageurl=" HTTP/1.1

Host: snacktv.de

Connection: close

Upgrade-Insecure-Requests: 1

RESPONSE

By default, the image format is determined by its magic number. To specify a particular image format, precede the filename with an image format name and a colon (i.e. ps:image)... ... or specify the image type as the filename suffix (i.e. image.ps). Specify file as - for standard input or output.

The reason I sent this request was because in the initial proof of concept XML file we're restricted to the URL entity through a double quote (or potentially a single quote). If we send a double quote, we could force the server to escape this scope and have write access to where the command would be written (see proof of concept content above).

Huh! No-way! This was running ImageMagick! Did I just break the execution somehow? Is this command line content? I should send additional content...

REQUEST

GET /imged/getImg.php?imageurl=";ls HTTP/1.1

Host: snacktv.de

Connection: close

Upgrade-Insecure-Requests: 1

RESPONSE

By default, the image format is determined by its magic number. To specify a particular image format, precede the filename with an image format name and a colon (i.e. ps:image)... ... or specify the image type as the filename suffix (i.e. image.ps). Specify file as - for standard input or output. [redacted] [redacted] index.php getImage.php [redacted] [redacted]

The reason I sent the string listed above was to escape the first commands scope. In a Linux environment you can append the semicolon to your initial command and begin writing a second command. This is useful for attackers because it allows for execution outside of the initial predefined content.

At this point I was stoked. I had achieved command injection for the first time in my hunting career. During pentesting prior to this I always felt silly for sending quotes and semicolons in attempt to achieve command injection, but this completely changed my viewpoint.

Shortly after the find I reported this through HackerOne's bug bounty program for Yahoo. I received a response within 24 hours and had the bug fixed in an additional six.

Overview

You thought there was going to be a step four? No, no. We're ethical hackers... remember?

After attacking SnackTV it made me realize how serious botched implementations may be. The server was not vulnerable to ImageTragick through the generic method because it didn't follow the standard format, but instead something very similar and custom. If you can't figure something out that you're sure is vulnerable sometimes it's good to reset your mind and attack it from the roots. What characters will it allow and which will it fail? How long can your input be? What varies in the response?

It's very invigorating and refreshing attacking such a juicy platform after spending days withheld in Yahoo's large applications. Special shout out to dawgyg for spending his free time looking at this application with me.