To preface this article I’d like to give a huge shout out to Yahoo’s paranoids and everyone involved in their bug bounty program. Due to certain privacy conditions I’ll no longer able to participate in their program (no, I was not banned), but for the past year and a half I almost exclusively worked on their platform. Over the entirety of my experience they’ve served as both an educator and a sandbox all-the-while boasting impressive payout, triage, and validation times. If you’ve never participated in bug bounty or don’t know too much about the whole ordeal then I’d suggest reading the guidelines and going at it. As they say – “hack to learn, don’t learn to hack”.

The Process

When doing reconnaissance one of the first things I try to do is get a grasp for what is running on the server side of things. Although this doesn’t necessarily give me any bounties directly, it can help in later exploitation techniques or identification of vulnerabilities tied to CVE’s and publicly disclosed issues in the software. An example of this would be local file inclusion on a LAMP (Linux, Apache, MySQL, and PHP) stack that could be escalated to remote code execution by polluting any log file with something like <?php phpinfo(); ?> then using the vulnerable function (e.g. include_once or require_once) to execute the PHP.

There are different ways to go about identifying the stack – a few are…

- Attempt to identify HTTP response headers manually via BURP or another proxy (e.g. Server: Apache-Coyote/1.1)

- Using Shodan to mass-identify HTTP response headers with a tied host name (e.g. hostname:example.com “Server: Apache-Coyote/1.1”)

- Run Google dorks against the website using file extensions or different indicative queries (e.g. filetype:php site:example.com)

- Supply specific content relative to the guessed backend in order to get the website to respond in a way that validates your assumption

The actual target for testing was Yahoo’s small business platform. After a while I was able to identify they were running NodeJS on the user control panel after bumping into a page that was misconfigured and exposed a template that should’ve been executed on the server, but was instead served to the client. I’m not sure why this happened but it did.

Now that I knew it was running NodeJS on the panel portion I could proceed with testing and save some time by not having to “hail Mary” everything.

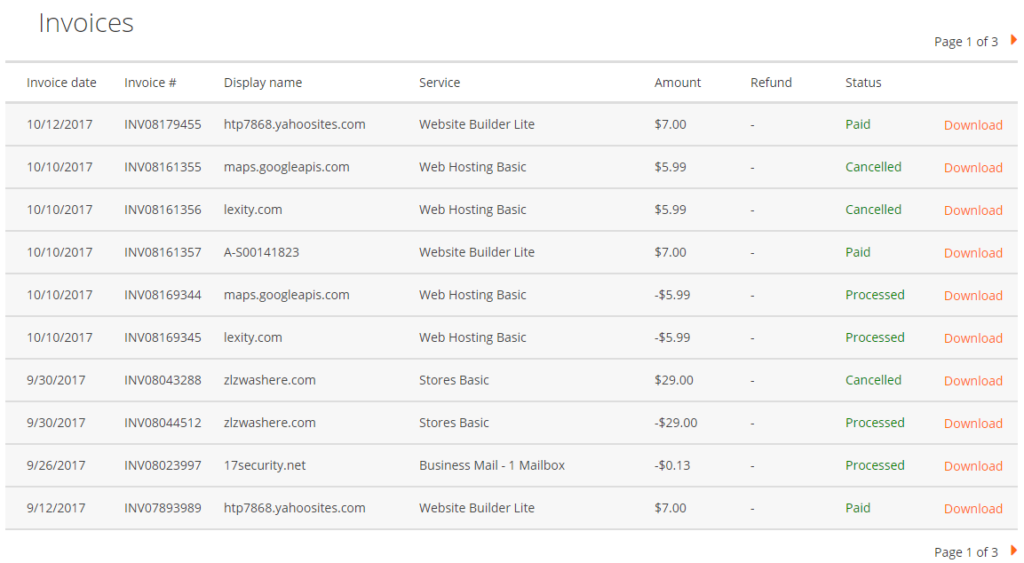

There was one endpoint I had seen after purchasing a subscription that I’d never been able to exploit. It was very a very simple webpage that displayed a invoice PDF to the user after they clicked “download”. The reason this function would be fun to exploit would be that it displays billing information about the user.

The endpoint to view the PDF looked like this:

https://www.luminate.com/my-services/invoices/INV08179455/pdf

Now the standard thing to do at this endpoint would be to change the “INV08179455” argument to a PDF that wasn’t actually yours. If this IDOR (indirect object reference) was successful then we could view potentially any invoice. As you would guess this was not successful and was probably done by 90% of hackers who purchased a subscription on Luminate, but I was not satisfied with the results as it was such a fun looking function.

One of the questions I had was “why use PDFNAME/pdf and not PHPNAME.pdf?” – the most immediate answer was that the function that processed this validated that the user owned the PDF before serving it. At the time, this conclusion made complete sense, but would be confirmed incorrect as we moved forward.

Since I was able to identify that it was running NodeJS I could recall specific things about the system in place and one of those was that Node took parameters/arguments within what we’d normally perceive as a directory. An example would be the following:

NodeJS "/view/ID" is sort of the equivelant of PHP's "/view.php?id=ID"

With this information we could move forward and supply whatever we could in order to get the system to do something it was not supposed to do. After a couple minutes of supplying control characters for SQL injection and viewing the source to make sure it didn’t make some strange call to a PDF via the browser I was able to determine one thing:

https://www.luminate.com/my-services/invoices/.%2fINV08179455/pdf https://www.luminate.com/my-services/invoices/INV08179455/pdf

… both of these HTTP requests returned the same results. Although it is standard practice in many web servers to just process the “.%2f” as “./” and make it hit the exact same directory and argument, Node was potentially taking the “.%2f” as an actual argument in the invoice ID directory parameter.

If this were true it would suggest that the invoice ID directory parameter was fetching some sort of file in order to display the PDF and the user was able to supply “.%2f” and potentially “..%2f” to specify what directory to pull from. In order to “sort of” confirm this I sent the following request.

https://www.luminate.com/my-services/invoices/..%2fINV08179455/pdf

As expected it returned “404 – not found” just like any invalid PDF argument would. In order to further confirm this I needed to find out the directory the PDF file was inside of, and in order to actually do that I probably do a LOT of guessing. OK – first try, no wordlist, here goes nothing…

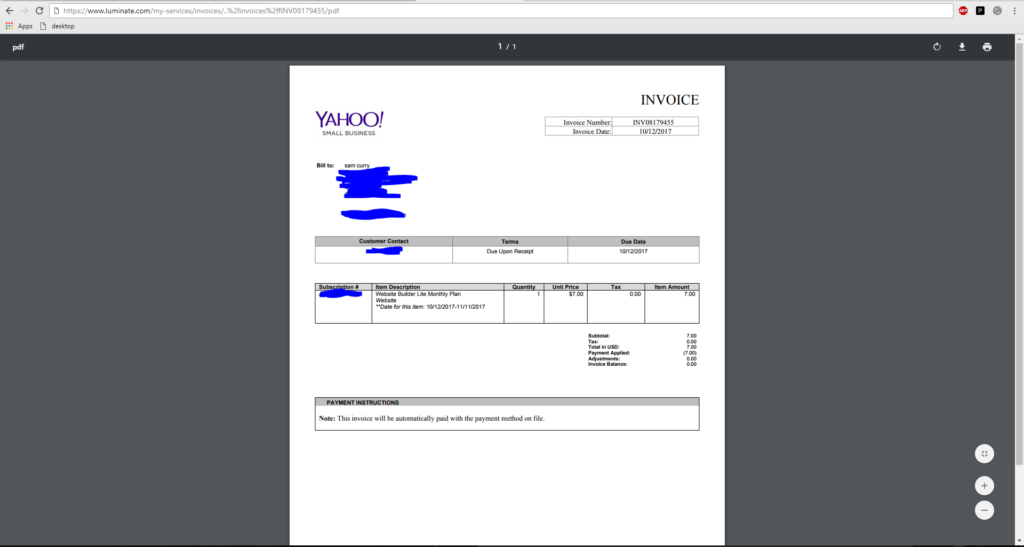

https://www.luminate.com/my-services/invoices/..%2finvoices%2fINV08179455/pdf

Hey! 200 OK! It was my PDF!

After seeing this I wasn’t too excited because if you notice the directory right before this is “invoices” so it could’ve potentially been somehow processing this as a normal HTTP request and running the page normally. In order to verify that this wasn’t the case, all I had to do was the following…

https://www.luminate.com/my-services/invoices/..%2f..%2fmy-services%2finvoices%2fINV08179455/pdf

This request returned “404 – not found” which meant that the server was probably fetching the file from a folder called “invoices” with an unknown folder beforehand. After thinking it over for a few minutes one of the things I thought of was that the server using some string of identifying information like an account ID or email to create a folder specific to the user which would be used as an index to fetch files from. That way, when the user called the endpoint normally, it would supply “accountID/invoices/ID” and disallow any attempt to include someone else’s PDF through modification of the number. The following are a few unsuccessful attempts to exploit this…

https://www.luminate.com/my-services/invoices/..%2f..%[email protected]%2finvoices%2fINV08179455/pdf - raw email https://www.luminate.com/my-services/invoices/..%2f..%2faccountIDhash%2finvoices%2fINV08179455/pdf - account ID per control panel field https://www.luminate.com/my-services/invoices/..%2f..%2fsamwcurry%40gmail%2ecom%2finvoices%2fINV08179455/pdf - url encoded email

None of them worked. After a few hours I got sort of bored of the endpoint and decided to look around. What I discovered pushed me to finally exploit the issue.

https://www.luminate.com/order/confirmation/..%2forders%2forderId - same behavior https://www.luminate.com/my-services/more-info/json?uid=../subscriptions/subscriptionID - same behavior https://www.luminate.com/my-services/edit-payment-method?uid=../paymentmethods/paymentMethodID - same behavior ... etc ...

If I was able to identify the root folder for all of these trailing directories then I could potentially fetch from other users. The issues and questions present with that, however, are the following…

- What if the string is something that cannot be guessed? (e.g. 32 character alphanumeric hash)

- How will the attacker identify the subscription ID?

- If this behavior is present will it even be exploitable in the wild?

Time to do some digging! After looking around for a long time I remembered something I had seen in the domain control panel portion of the website. In one of the functions that allowed you to update a domains information you could change the domain name to something you did not own and it would respond in a pretty interesting error…

{"error":"Id [email protected]#vj does not have permission to modify the domain example.com."}

Why was there a trailing #vj at the end? To be honest, after exploiting this, I’m still not sure… all I know is that it was present. This endpoint was not exploitable and did not follow the same practice as the control panel because it (1) filtered all domain related arguments and (2) seemed to be executing SQL queries or something similar due to the “id” parameter (this was just a guess).

The moment of truth would be using this email with the appended mysterious “#vj” (or url encoded %23vj) to access my personal files, and after confirming the behavior, another users files.

https://www.luminate.com/my-services/invoices/..%2f..%[email protected]%23vj%2finvoices%2fINV08179455/pdf

Hey! It was my PDF! This meant that the setup was something like this…

- [email protected]#vj services - serviceID (full folder [email protected]#vj/services/serviceID) invoices - invoiceID (full folder [email protected]#vj/invoices/invoideID) paymentmethods - paymentMethodID (full folder [email protected]#vj/paymentmethods/paymentMethodID)

The second moment of truth would be confirming that I could indeed fetch someone else’s PDF using the full payload. The easiest way to confirm this would be to just copy the endpoint with the final payload to load from my own account and load it on a separate account.

This behavior was successful. The real question, now, was how could the attacker realistically exploit this?

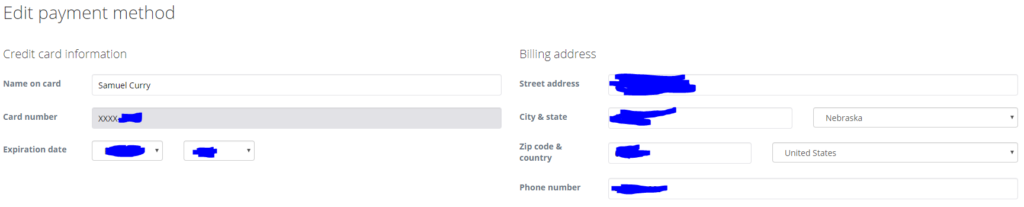

After pondering the question and chaining a ton of things together I was able to finalize the impact as the following: an attacker, with only the victims email, could view another users payment information (last four numbers of their credit card, expiration month, billing address, etc). I’ll save you the drawn out details of how long it took to chain these issues together but I will give you the final reproduction steps..

- Attacker utilizes the following endpoint. This endpoint requires (1) the victims email and (2) a tool like dirsearch. Although this did require brute forcing, it only took somewhere around a maximum 10,000 requests. There is no restrictions to brute forcing this portion of the site so I was able to do this in very little time.

https://www.luminate.com/order/_cart/changecart?id=../../[victimEmail]%25%32%33vj/subscriptions/[guessableVictimSubscriptionNumber]&to=bmg4a_t1m

The purpose of the above endpoint was to simply modify an existing subscription number to another one. This could be utilized using any current or expired subscription numbers, so the victim simply had to have (at some point) purchased something on Yahoo’s small business platform. - The attacker receives the following response…

{"success":"Cart successfully updated","result":{"type":"change","subscriptions":[{"subscriptionNumber":"[subscriptionNumber]","addProductInvoice":"","removeProductInvoice":"","meta":{"paymentToken":"[payment token -- this is a 32 character alphanumeric hard to guess ID]","oacs":"[oacs]","pvtreg":"[domain]","domain_name":"[domain]","bizmail":"[domain]","hosting":"[domain]","domain":"[domain]"},"addRatePlans":[],"removeRatePlans":[]}],"user":{"userId":"[victim email address with #vj]"},"meta":{"flow":"","upgradeFlow":false},"id":"[unique ID of the request transaction]"}}The above response includes the “payment token”. This is a 32 character alphanumeric hard-to-guess token that allows a normal user to modify a payment method via the below endpoint.

- In the final step of our scenario the attacker puts the payment token in the below endpoint along the directories we discovered during testing…

https://www.luminate.com/my-services/edit-payment-method?uid=../../[email]/paymentmethods/[payment token]

Remember: in order to get to this final step all we really needed was the victims email address.

Conclusion

The Yahoo small business platform was storing user information in a set of directories that were protected simply by obscurity. The attacker, with knowledge of the victims email, could run an wordlist against a very predictable/guessable service ID and receive information from the response in order to view the victims payment information. The fact we were able to tell this was running on Node allowed us to structure the attacks and eventually get it to respond the way we wanted it to.

Why didn’t you fetch /etc/passwd?

This is a question that I think will come up eventually. The reason I did not fetch “/etc/passwd” or any system file was because the file fetching was done through an API over GET. I was able to confirm this using the following tests…

- The query would fail if I did “VALIDID&” but not when I did “VALIDID?&”

- I was able to traverse from directories that did not exist. Try this in your web browser: http://example.com/directorytThatDoesNotExist/../ – it will return you to the index

Timeline

October 21st – submitted

October 23rd – triaged

November 8th – fixed

Pending bounty